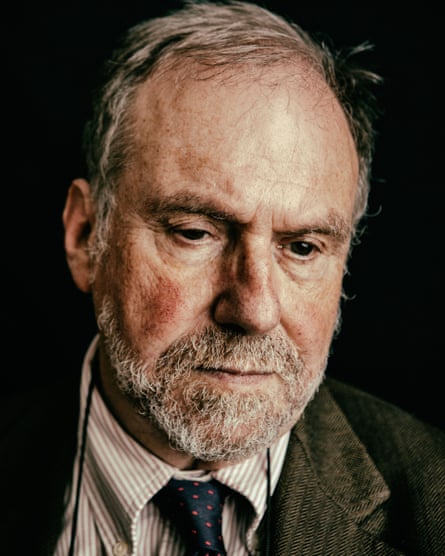

Tavistock trust whistleblower David Bell: ‘I believed I was doing the right thing’

The psychiatrist behind a critical report on the gender identity unit at the NHS trust on the efforts to silence him and his concerns about children’s access to treatment

To talk to David Bell is to have some small sense of what it might be like to be his patient. At 70, his energy puts mine to shame. He cycles everywhere. His diary is full. I’ve rarely interviewed someone so engaged (there are days when he emails me several times, each message more exacting than the last). But ask him a question and he’s unlikely to rush in. Certainty is not a given. His open-mindedness belongs to someone far younger. Above all, he is so calm: a reassuring presence. There are times during our conversation when it’s hard to believe we’re discussing experiences that must have caused him so much anxiety and even, at moments, some fear.

Bell, a distinguished psychiatrist and practising psychoanalyst, is the doctor who in 2018 wrote a controversial report about the activities of the gender identity development service (GIDS), a clinic at the Tavistock and Portman NHS foundation trust in north London, where he worked in adult services from 1995 until his retirement earlier this year. GIDS, the only clinic of its kind in England, specialises in treating children with gender identity issues and in recent months has been in the news even more than usual. Last December, a judgment by the high court ruled that those under the age of 16 were unlikely to be mature enough to give informed consent to the prescription of puberty blockers (such drugs delay the development of secondary sex characteristics in patients, in theory enabling children more easily to transition into their desired gender identity as an adult). This ruling, the result of a judicial review brought by 23-year-old Keira Bell – born female, she was prescribed blockers by GIDS at 16 and now regrets her transition – has effectively curtailed medical intervention for children with gender dysphoria. (The Tavistock is to appeal; the case will be heard in June. David Bell will be what is technically called an intervenor in the appeal, which means he can give evidence.)

Bell’s report anticipated the concerns of the high court and he feels vindicated by its judgment. “It was jaw-dropping,” he says. “Because it was very strong.” As he read it, he was struck by details that have not been widely reported, particularly those involving a lack of data, a problem he had raised himself (GIDS was unable to produce for the court any data relating to outcomes and effects, whether desirable or adverse, in children who had been prescribed puberty blockers; nor could it provide details of the number and ages of children who had been given them). But the experience was painful, too: “I felt concerned that we’d moved away from the values [of care] the trust has embodied for so long.” He is astonished the judgment seems to have had so little effect on the organisation of GIDS. “Ordinarily, heads would roll,” he says. “The management structure has changed slightly, but it feels like window-dressing.”

But whatever the court’s verdict, it cannot change the fact that the organisation to which Bell devoted the greater part of his working life did not respect his rights as a whistleblower. Nor has it taken the heat out of the debate about the medical treatment of trans children – if anything, the discourse has only grown more entrenched – which is why he’s talking to me now. This is the first time he has spoken in detail about his experiences: about how he came to write his report and the grave consequences that doing so had for him. His retirement means that the threats of disciplinary action against him are over. He is free, at last, to say what he likes.

Writing the report was, he says, a matter of conscience. In 2018, 10 GIDS staff brought their worries to him unsolicited, a figure he estimates to be around a third of those then working there. He had no choice but to act and would do the same again. Nevertheless, it was not easy. Far from being grateful to him for alerting it to a potentially dangerous situation, the trust’s position appeared defensive – having read the correspondence involved, perhaps aggressively so – almost from the start. It tried to silence him and instituted proceedings against him. Was he frightened? Yes and no. “I believed I was doing the right thing,” he says. “I never doubted that, and most of my colleagues in the adult department supported me, so when I went up to my floor at the Tavistock, I could be oblivious and get on with my work. The real betrayal wasn’t of me personally, but of the trust’s duty to whistleblowers and to its wider mission [since 1920, the Tavistock has specialised in talking cures]. But the thing that enables you to sleep at night is a good lawyer.” To pay for this lawyer, he launched two crowdfunding appeals.

How, exactly, did the trust attempt to silence him? The trust told the Observer that it is proud of the GIDS service, which is committed to providing high-quality support and care for young people experiencing issues with gender dysphoria, and that the claims made by Dr Bell are historical and were dealt with following proper processes at the time. It vigorously denies that any steps were taken against Bell for being a whistleblower. It says that it has a duty to safeguard its staff, who have faced intense, personalised and upsetting harassment, and has taken a series of actions, following proper processes, to do this.

By Bell’s telling, its approach was at once Kafkaesque and cack-handed. In the months after he delivered his report, a book to which he had written an introduction was removed from the Tavistock’s library. When he spoke at a conference about de-transition in Manchester, a member of GIDS’ staff travelled there, he says to spy on him. “They wrote it up very accurately,” he says, with a laugh. Finally, he was told that he was not allowed to write about, or to talk in public about, anything that wasn’t directly connected to his NHS employment, “which sounded odd to me… was it the case that if I was going to write a paper about the psychology of King Lear, I’d have to ask permission?” (As his lawyer informed him, this was against the terms of his contract.)

The story begins in February 2018, with a knock on Bell’s office door. “I was often the person people came to when they had problems,” he says. Having worked as a consultant at the Tavistock for more than 25 years, he was one of its most senior doctors: for 10 years, he was in charge of its scientific programme; in 2018, he was also an elected staff governor of the trust, for the second time. Of the 10 GIDS staff who would talk to him over the course of the next seven months, only the first saw Bell at the Tavistock; the others, who spoke of intimidation, worried about being seen. What did he make of what they told him? “My blood ran cold. Their concerns were similar, but not in a choreographed way. One or two were severely troubled.”

Among these concerns were the fact that children attending GIDS often seemed to be rehearsed and sometimes did not share their parents’ sense of urgency; that senior staff spoke of “straightforward cases” in terms of children who were to be put on puberty blockers (no case of gender dysphoria, notes Bell, can be said to be straightforward); that some were recommended for treatment after just two appointments and seen only infrequently thereafter; some felt that GIDS employed too many inexperienced (and inexpensive) psychologists; that clinicians who’d spoken of homophobia in the unit were told they had “personal issues”. One told Bell that a child as young as eight had been referred to an endocrinologist for treatment. “I could not go on like this… I could not live with myself given the poor treatment the children were obtaining,” said another.

Was he surprised? How much did he know about GIDS before these conversations? (The clinic, which was established in 1989, had grown hugely during his time. In 2009, it saw 80 patients. By 2019, this figure had risen to 2,700.) “That’s a good question. It started as a small service, then it became nationally funded; a contract with NHS England meant a guaranteed income. It was peculiar. You could see that everyone knew about it and yet no one wanted to know about it. In the adult department, there was a sense that we didn’t want to find out what went on there, because we might not have liked it if we did.”

Bell wondered what he should do. “In July, I met with hospital management. I told them I would write a report. They said: OK. While I was writing it, I contacted GIDS. I needed to know some basic stuff: the number of patients they’d seen; their gender; what psychiatric problems they may have had.” He received no answers. “I then got a rather unpleasant letter from Paul Jenkins, the trust’s chief executive. It said that GIDS was very busy and that its staff were not obliged to answer me.” Was it that GIDS didn’t have the data or that it didn’t want Bell to have it? “Both.”

In September, Bell sent his report to Jenkins and to Paul Burstow, the chairman of the board. For unspecified legal reasons, he says, they forbade him to send it to the council of governors, which oversees the board. “That was when I got myself a lawyer,” says Bell. His lawyer told him that, on the contrary, a failure to send it out might make him culpable in the event of any future legal case taken against the trust. When he did so, however, he received what felt like a “very hostile and threatening” note from Burstow. Nevertheless, the report was discussed at the next council, where it was agreed that a review of GIDS would be led by Dinesh Sinha, the trust’s medical director. In spite of this, in November 2018, Bell received two letters threatening disciplinary action. One of the grounds was “bullying”. He was not told whom he had bullied. He was also asked to agree not to speak any further to Sonia Appleby, the trust’s director of child safeguarding. (Appleby is bringing a whistleblowing claim against the trust in which she alleges that when she made “protected disclosures” regarding concerns raised by GIDS staff over patient safety, she was subjected to detriments.)

While Sinha’s review was taking place, Bell asked for its terms of reference. He wanted to ensure that those who’d talked to him could speak to the review safely, that their anonymity would be protected. He says he got no response. Bell wrote to staff at GIDS, reminding them of their right, as NHS workers, to speak confidentially. At this point, he says, the trust “went ballistic… they interfered with my emails so I couldn’t write to them again”. The trust’s review delivered its report in February 2019. Initially, Bell was not allowed to see it. He was then given 30 minutes to read its 70 pages (it was later leaked to him in full). “There was still no data. It mentioned intimidation, but no action was [to be] taken. However, it did acknowledge the inappropriate involvement of trans ideology groups in the work of the service.” The report was approved by the board and the council of governors, although one consultant psychotherapist, Marcus Evans, accused the trust of having an “overvalued belief” in GIDS expertise and resigned. Soon after this, Bell’s report was leaked to the press. “That disturbed me, until I read [the article],” he says. “The reporting was accurate. I started to think it was a good thing.” He says the trust began to suggest that Bell was unqualified to write such a report and to suggest that the cases in it were hypothetical. (They were not.)

In early 2020, procedures were set up for disciplinary action to be taken against Bell. “All the grounds were in connection with my activities as a whistleblower,” he says. In the meantime, Bell announced that he would retire, as he’d always planned to, in June 2020. But then the pandemic hit; wanting to see his unit through it, he decided to delay his departure until January 2021. The trust attempted more than once to set a date for the hearing, but these were always dropped. Bell felt all this was just for show.

His retirement was only weeks away.

Last January, he retired as planned, only a month after the Keira Bell judgment. He had long believed a case would be brought against the trust, though he thought the most likely scenario was that a former patient would sue for damages (Keira Bell instigated a judicial review). “It was inevitable,” he says. “I warned the trust of this.” But the Keira Bell judgment has done little to alleviate his concerns. Whatever the outcome of the appeal, he believes more questions must be asked, particularly about the rise in the number of girls presenting at the clinic (three-quarters of patients are now girls; the gender balance used to be closer to 50:50). “We do not know why this is happening.” He worries that too much emphasis is placed on gender and not enough on sexuality – “the children are often gay” – and he continues to be anxious about co-morbidities such as anorexia, autism and history of trauma in its patients. “Some of the children are depressed. It’s said that it’s their gender that is the cause of this, but how do we know? And why don’t we try to treat that first?”

Bell is not against puberty blockers per se – “a doctor should never say never” – but he believes that halting puberty only makes it more frightening to the child: “The child will never want to come off the hormones and 98% do now stay on them. This could be a dangerous collusion on the part of the doctor. The body is not a video machine. You can’t just press a pause button. You have to ask what it really means to stop puberty.” It should be possible, he believes, to manage the distress of a child who is suffering gender dysphoria in a less interventionist way, until he or she is an adult and can make a decision: “Consent is the issue here, nothing else.” He does not doubt that some patients will want, and need, to transition in the future. But, he says, not all children with gender dysphoria are trans. The two have been elided. More work needs to be done locally. “Gender dysphoria clinics should be part of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and available nationwide,” he says. “At the moment, children who are suffering extreme distress in relation to their bodies are sent to the Tavistock and the problem then goes away at local level, where psychotherapy services are on their knees.”

There is anger on both sides of the debate. But given his politics – Bell describes himself to me as a “Corbyn-supporting Jew” – he has been most shocked by the reluctance of the left to engage with the issues. “They think this is to do with being liberal, rather than with concerns about the care of children. Mermaids and Stonewall [the charities for trans children and LGBTQ+ rights] have made people afraid even of listening to another view.” It surprises him that the left is unwilling to consider the role played by big pharma. In the US, a journal that published a paper about the effect of puberty blockers on suicide risk recently had to disclose that one of its co-authors received a stipend from the manufacturer of another drug.

When he appeared on Channel 4 News earlier this year, Bell was asked if he feared being on the wrong side of history. “I’ve often thought about that question,” he says. “It’s a good one. Psychiatry has a sad past. Homosexual men were given behavioural therapies and so on. But history isn’t always right. What matters is the truth. I hate the weaponisation of victimhood, the fact that the fear of being seen to be transphobic now overrides everything.” The current campaign to ban so-called gay conversion therapy is, he believes, likely to become a Trojan horse for trans activists who will use it to put pressure on any clinician who does not immediately affirm a young person’s statement about their identity, decrying this, too, as a form of “conversion”. For Bell, the prospect of not being able to talk openly about such things is a tyranny: just another form of repression. “This is about light and air,” he says. “It’s about free thinking, the kind that will result in better outcomes for all young people, whether transgender or not.”